Revolutionizing Robotics

Published 03.23.2021

by Thomas Speicher

Writer/Video Producer

Curiosity fuels Fletcher Ewing.

As a kid, it drove him to meticulously build and competitively race Soap Box Derby and remote control cars. As a college student, it pointed him to plastics. As a professional, it led him to devise and develop innovative products. Today, it inspires him to “shoot for the moon.”

The 1998 Pennsylvania College of Technology graduate is thriving as a senior mechanical engineer in Silicon Valley at X, The Moonshot Factory. The company formerly known as Google X comprises engineers, inventors and entrepreneurs whose expectations defy gravity. Their lofty objective is to build and launch “technologies that aim to improve the lives of millions, even billions of people.”

Current initiatives at X – a subsidiary of Alphabet, Google’s parent company – include driverless cars, delivery drones and internet access via light beams and balloons. Ewing’s assignment is the Everyday Robot Project, which aims to create robots that can operate in unpredictable settings, such as homes and offices. Unlike today’s robots, which are built to perform specific functions in structured environments, X wants its machines to possess the humanlike capacity to learn and adapt.

“We’re focused on developing an end-to-end robot system that requires us to integrate many different components like the hand, arm, body, head and computer to work together to do something reliably over time in real-world, unstructured environments,” Ewing said. “We see robots as tools that we can put to work to extend humanity’s capabilities.”

X describes the development of such general-purpose robots as “tackling and integrating some of the hardest hardware and software challenges in the field of robotics.” The herculean job description doesn’t spook Ewing. Instead, he savors it.

“With problems come solutions, and X’s mission is to solve difficult problems,” he said. “You have to accept you may not get it right after multiple attempts. In my opinion, failure is part of being an engineer and has been part of my experience since the beginning.”

It’s difficult to determine “the beginning” from Ewing’s resume. Is it his graduation from Penn College’s renowned plastics program? His development of a device that identified the remains of the world’s most-wanted terrorist? His work on components for a high-end vehicle? His creation benefiting swimming pool owners? The answer is “none of the above.”

Childhood activities inspired by deep curiosity conceived his engineering acumen. Growing up, Ewing’s prized possession wasn’t a toy. It was a used set of the Encyclopaedia Britannica.

“For as long as I can remember, I’ve had intellectual curiosity in things, people and history. Before you could ‘Google it,’ I would have my face buried in books to find out things,” said Ewing, who earned a bachelor’s degree in plastics and polymer engineering technology. “I’ve always been very interested in how things work and the science behind it. I grew up during a time when kids were outside playing and figuring things out on their own, which left an incredibly broad and blank canvas to fill.”

Fill it he did. With his older brother, Nathan (a 2002 automotive technology graduate of Penn College), and father, Dalas, Ewing spent countless hours in his native Selinsgrove manufacturing Soap Box Derby and remote control cars. Both endeavors taught him to embrace, not shrink from, challenges.

The Soap Box Derby cars required handling wood and fiberglass to finalize the body and troubleshooting pulleys, bell cranks and cables to install the control and brake systems. Painting the car so its finish produced the least aerodynamic drag also consumed considerable time. Testing and fine-tuning preceded the races, which took Ewing’s family throughout Pennsylvania and to the national championships in Akron, Ohio.

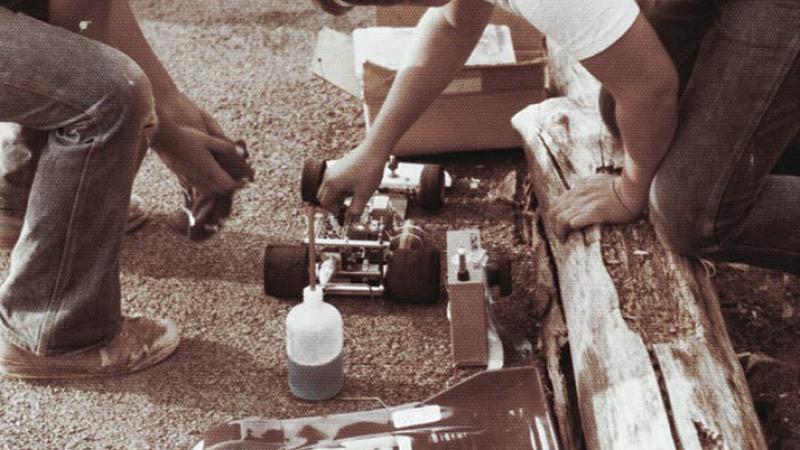

When he was 11, Ewing “graduated” to remote control cars. But they weren’t ordinary RC cars to run on the kitchen floor. He built one-eighth scale, nitro gas-powered cars for road races that could exceed an hour. Choosing and incorporating optimal tire compounds, fuel type, motors, gearing and exhaust systems were critical for racing success. Ewing and his brother excelled, winning several events and earning sponsorship from Delta Manufacturing.

They learned the enduring virtue of patience while testing their mechanical aptitude and ingenuity.

“My father was extremely fussy and had a lot of pride in quality and workmanship, along with a positive attitude,” Ewing recalled. “So in the process of working on the cars and racing, he instilled that same mindset into my brother and me.

“You have to be patient and make sound decisions. Rushed judgments on product design or engineering can cost companies thousands of dollars and their reputation.”

Shortly after graduating from high school, Ewing put his engineering aspirations on hold. The passing of his father prompted him and his brother to become full-time employees of the family’s building products company. The family sold the business’s assets a few years later, opening Ewing’s opportunity to attend Penn College.

The “uncommon and specified focus” of the plastics and polymer engineering technology program attracted him to the school. Penn College is one of only six institutions nationwide offering plastics degrees that are accredited by the Engineering Technology Accreditation Commission of ABET. The college is also home to the Plastics Innovation & Resource Center, an internationally recognized provider of plastics training, research and development, and industry partner programs.

“I wanted to get into new product development involving plastics materials or composites in some shape or form,” Ewing said. “The labs and hands-on work allowed us to physically test theories or the material science and gave us the freedom to choose related paths and interests.

“I’m very thankful for my experience at Penn College. It has given me the right tools and direction to become what I am today.”

Combining theory with extensive hands-on training in labs dedicated to various plastics processes is what distinguishes Penn College’s program, according to Kirk M. Cantor, professor of plastics and polymer technology.

“I tell my students all the time that there are folks who understand the science really well but can’t run the machines. Then there are people who can run the machines but aren’t as strong with the science,” he said. “Our students straddle both worlds. They understand the science, can run the machines and troubleshoot effectively.”

Cantor remembered “Fletcher Ewing the student” as diligent and possessing a good attitude. He described “Fletcher Ewing the alumnus” as the embodiment of the varied, rewarding opportunities available to graduates of the plastics program.

“Pretty much everything dealing with electronics and technology has plastic components involved,” he said. “Because our students are working with state-of-the-art plastics technology, they are exposed to ancillary types of technologies. Many graduates do migrate from working directly with plastics to focus on other technologies, and they do well. The opportunities are always there for anyone like Fletcher, who is good at what they do and works hard.”

I grew up during a time when kids were outside playing and figuring things out on their own, which left an incredibly broad and blank canvas to fill.

Ewing’s degree steered him to the automotive industry and its increasing reliance on plastics to reduce vehicle weight for better gas mileage. He was a product development engineer for top suppliers of under-hood and interior components. The role included trips to Germany for the Mercedes-Benz W164 program, which produced the second generation M-Class luxury SUV.

“It was fun going to Germany and working directly with Mercedes-Benz in Sindelfingen, getting behind-the-scenes tours and seeing vehicles that were not yet released to the public,” he said. “I loved Germany, but eventually the hours and travel were not a great fit for me.

“Working in the industry was a good start and taught me much about manufacturing and design for manufacturing and assembly, which aided my career path.”

The aquatics industry was the next stop on that path. For two companies, Ewing served as lead mechanical engineer of new product development. At Aquatron Robotic Technology in Delray Beach, Florida, he produced robotic swimming pool cleaners and water treatment devices. Nine years later, at Fluidra in San Diego, he designed and developed the Polaris Quattro, an autonomous submersible pool cleaner, launched commercially in January 2020.

“It involved a big team of people to make it happen,” Ewing said. “It was a great experience and has had great reviews after one season on the market.”

With its four big wheels and plastic body, the machine resembles a toy monster truck in size and shape. Powered by a booster pump, the Polaris Quattro scours a pool’s bottom and climbs its sides to devour any debris. The pool owner doesn’t break a sweat. For them, it’s like hiring Aquaman to vacuum.

Between his two stints in aquatics, Ewing helped to create a tool used by real heroes. Working for Cross Match Technologies in Palm Beach Gardens, Florida, he played a key role in designing, developing and selecting materials for the SEEK Mobile Biometric Device. U.S. Navy Seals employed the instrument during the 2011 mission that killed Osama bin Laden, the mastermind of the 9/11 attacks, which claimed nearly 3,000 lives on U.S. soil.

The Seals relied on the device – a small PC combined with proprietary biometrics hardware – to positively identify bin Laden’s remains after their successful raid of his compound in Pakistan.

Since it was built to withstand drops, water and sand intrusion, and extreme temperatures, Ewing’s team realized its invention would appeal to the military. They didn’t know about the device’s role in identifying the Al-Qaeda leader until a company-wide meeting a few weeks after the raid.

Aiding humanity is Ewing’s ultimate goal in his current role with the Everyday Robot Project at X. His innate curiosity and unquenchable thirst for innovation convinced him to apply for the senior mechanical engineer position in the fall of 2019.

“X has a long history of bringing together hardware and software to create breakthrough solutions,” he explained. “I was thrilled to join a renowned company working on such a rewarding and challenging project. Machine learning and robotics could one day help us find new solutions to some of the biggest challenges facing the world – from finding new ways to live sustainably, to caring for loved ones, to tasks we’ve not even imagined.”

Whether he is prototyping inside X’s 20,000-square-foot workshop in Mountain View, California, or designing from home due to the COVID-19 pandemic, Ewing’s days consist of hands-on work with components, interactions and meetings with team members, and hours devoted to research and development. That effort has produced tangible results.

The company’s offices are populated by several robot prototypes, all of which bear a slight resemblance to the “Number 5” robot featured in the 1986 classic film “Short Circuit.” Unlike that fictional machine, these mobile robots don’t talk, but they are sleeker and smarter. Current testing requires the prototypes – relying on artificial intelligence software and equipped with cameras, sensors and one “arm” – to grasp and accurately sort waste into bins earmarked for landfill, recycling and compost.

“We have tens of thousands of virtual robots running in the cloud to learn this task nightly,” Ewing revealed. “What’s gained in experience and learning is then transferred and shared to the physical robots. We have reduced contaminated waste from 20% to less than 5%. This proves that robots can learn tasks in the real world through practice versus having to code every new task, exception or improvement.”

It could be several years before the robots envisioned by X become part of the fabric of society. That reality doesn’t faze Ewing, thanks to lessons learned in childhood, augmented at Penn College and cemented in his various professional experiences.

“The challenge is what drives me and inspires me to be both creative and inventive in solving problems,” he said.

“I aim to be a lifelong learner and feed my curiosity as much as possible.”

Consider it fed.

Share your comments

Penn College Magazine welcomes comments that are on topic and civil. Read our full disclaimer.

We love hearing from you